Who should see a neurologist first: the sick or the vulnerable?

Once a year, Jessi Keavney goes to her neurologist. During the visit, the doctor asks if he has any new symptoms and does a complete physical examination. He observes the speed and range of his arm and leg movements, and assesses his ability to stand while sitting. As he walks, the doctor checks the swing of his arm, the length of his leg and his posture.

In general, this selection method represents a standard assessment of the motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease. But Keavney does not have Parkinson’s, or any other neurological disease.

At least, not yet.

What he has is a genetic mutation that puts him at high risk for Parkinson’s, which he discovered through a 23andMe test in 2013. Since then, Keavney has become an outspoken advocate for the Parkinson’s at-risk community, he traveled across the country to speak at conferences and participate in research. His regular visits to the neurologist allow him to be screened for signs of the disease, while keeping him informed about preventive measures and treatments.

All this makes sense. If someone told me that I had a high chance of developing a serious, progressive, incurable neurological disease, I would probably want to see a doctor too. But, as anyone who has actually tried to schedule such an appointment already knows, getting in to see a doctor, especially a specialist, can take months. Many doctors’ offices have waiting lists and are inundated with calls from potential patients, eager for their symptoms. still risk that needs to be assessed and dealt with.

Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s are two of the most common neurodegenerative diseases in the world, and seeking medical attention if you are at risk for one is not a mistake. Instead, Keavney and those in other vulnerable groups should get guidance on how to improve their well-being from a professional who takes their opinions into account. In addition, there is evidence to suggest that certain lifestyle changes can reduce the risk of dementia, and, for Parkinson’s disease, it has been proven that the right type of exercise can slow it down. development.

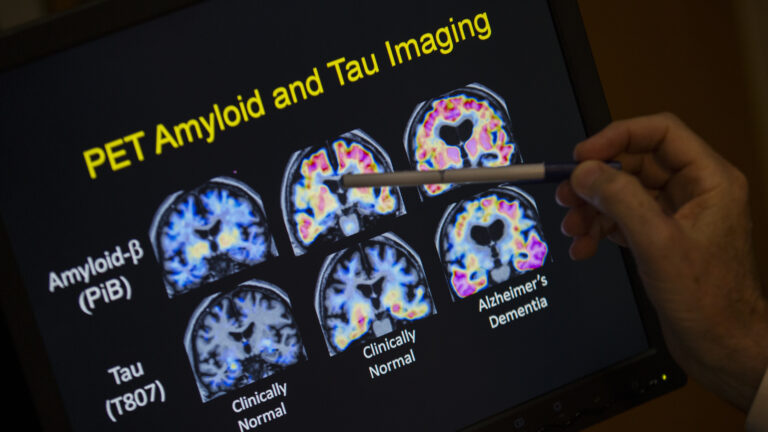

In addition, the medical condition is changing rapidly, as is the definition of “disease”. Drugs that promise to slow the rate at which Alzheimer’s progresses already exist (although their merits are still debated), and researchers have recently proposed that the stages of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s be reclassified to follow the presence or absence of symptoms of pathogens -potentially at risk) rather than based on symptoms.

However, as a neurologist, I often wonder how my patients would react if they knew that the person’s illness was not a reality but a possibility. the next day he received a consultation before them.

In the past, those with the ability to predict their neurological health outcomes with any confidence were part of a small group. A strong family history of the disease may alert a group of siblings or, more recently, the risk of the disease can be identified through commercial or prenatal genetic testing.

But all this is changing, and fast.

Genetic testing is now widely available, and in some cases, mutations that were previously thought to confer an increased risk of death have been reclassified as relatively inescapable messengers, thus triggering increased anxiety among carriers. At the same time, research – especially in the area of neurodegenerative diseases – has begun to identify abnormal molecules, known as biomarkers, which may begin to accumulate over the years ten before the signs of death are outwardly visible. Although guidelines currently do not recommend screening for these symptoms in those without symptoms, it is unlikely that companies and consumers will heed these recommendations.

Additionally, in recent years there has been a strong push for human research scientists to share study results with participants – including participants without current symptoms of illness. This means that healthy people who have participated in certain Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s studies can now easily find out if they have disease-related proteins, genes, or imaging changes.

Having participants research what science has revealed in their bodies is not a bad thing on its face (assuming proper explanations and counseling are provided). But, overall, the above developments are about to deliver more vulnerable people, each with no history of the disease in question, to already understaffed and overburdened doctors.

By 2021, approximately 117,000 physicians will retire, and earlier this year, the Association of American Medical Colleges released a report predicting that, over the next decade, the shortage will continue to increase. resulting in a shortage of approximately 86,000 physicians by 2036. Waiting times to see a neurologist may be longer than for other specialists and by 2025 it is expected that had a pre-existing neurologist deficit of 19%.

These estimates take into account the aging population, but not the increasing need for care that will certainly be accelerated by the influx of young people with a silent risk of eventually developing a neurodegenerative disease.

Like Keavney, many who know they may be at risk will seek advice on diet, exercise, medications and medical check-ups. Others will need regular check-ups to monitor the onset of disease, which may make them eligible for new research studies and treatments.

In tacit acknowledgment of this situation, neurological care centers targeting these vulnerable groups are springing up across the country, such as the Alzheimer’s Prevention Center at Weill Cornell, the Memory & Healthy Aging Program at Cedars- Sinai, and Women’s Alzheimer’s Movement Prevention. & Research Center Cleveland Clinic Nevada. But insurance plans do not always provide the necessary coverage for preventive health care, providing tests and services recommended by these clinics where most people do not have access.

Another disparity relates to the number of people enrolled in the research study. Women and underrepresented groups are less likely to participate in clinical trials and, therefore, less likely to receive clinical trial results – including results that may alert them to increased risk of disease, thus increasing the huge disparity in health care.

Supporting vulnerable populations without diverting resources from symptomatic patients will require the design and implementation of new health care delivery systems. For example, in recent years, group medical visits have begun to gain strength as opportunities for doctors to provide high-quality health counseling without strict time constraints for patient appointments.

A group visit model would allow care teams to provide up-to-date health recommendations and treatment – potentially delaying or preventing disease progression – without significantly increasing wait times, for of the sick. or at-risk, see a doctor. If anonymity was a concern, online meetings could replace in-person meetings, with participants remaining anonymous or off-camera. And, in both cases, these groups can be led by advanced practice providers, who generally have greater access than their physician colleagues.

Telemedicine may help fill the current gap in available resources for those at risk. Health services such as Neura Health and Synapticure now offer specialized appointments for many neurological conditions. Making neurosurgery part of the telephone offering can reduce some of the pressure on traditional clinics, ensuring easy access to expert guidance for those at risk without wasting waiting time.

But, without a doubt, the biggest help in caring for vulnerable communities will involve AI.

Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s are not, of course, the same, cookie-cutter diseases that affect every patient in the same way. On the contrary, as scientists are discovering, those with different genetic makeup, different biological processes and certain environmental conditions will continue to produce disease-producing strains, which continue to evolve. first, and may respond to treatment in completely different ways.

As more people at risk are identified and tracked over time, machine learning will allow for more information (family history, subtle symptoms, co-morbidities, test results and other data) to be analyzed. With this in mind, one can envision a future in which at-risk individuals receive personalized recommendations for disease prevention at the touch of a button, a process that physicians can oversee without sacrificing patient care. with diabetes. it has developed a neurodegenerative disease.

We’re not there yet, but we’re getting closer.

Meanwhile, Keavney, who has relatives with Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease on both sides of her family, plans to continue seeing her neurologist once a year.

“I may not be sick right now, but taking this kind of risk can make you feel like you’re cursed,” says Keaveny. And I absolutely refuse to feel that way.

Adina Wise is a neurologist and writer in New York City.

#neurologist #sick #vulnerable